Accommodations and Accessibility

Overview

Designing courses that provide equitable learning experience for all students supports the Georgetown mission to care for the whole person through our teaching. By foregrounding wellbeing, designing for accessibility allows us to attend to the social, emotional, intellectual, and scholarly development of our students, thus improving learning outcomes.

Students may be experiencing a range of challenges that can shift over the course of a semester, depending on the state of public health. These include:

- Interrupted access to social, emotional, and academic support networks

- Limited access to required technology and connectivity

- Limited access to private spaces suitable for concentrated study

- Heightened anxiety that can impede their capacity to engage with schoolwork

Accessible design can assist us in meeting our learning goals as well as further demonstrate to students that compassion and care can be central characteristics of a rigorous remote learning experience.

Accessibility in course design refers to the ways in which materials, content, delivery and assessment are designed such that they are easily reached by all students. Attention to accessibility means that the actual or potential obstacles to student learning are anticipated and mitigated in the course design process. For some students, accommodation needs are documented through the Academic Resource Center (ARC) at Georgetown. For others, obstacles to their full participation in the learning experience may arise unexpectedly, or may fall outside of the framework used by the ARC.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework that respects and complements the accommodations processes that some students pursue with the ARC; it emphasizes flexibility, dynamism, and communication both in the design process and in the course delivery phase. While individual students may have documented accommodations related to their learning needs, UDL asks us to consider how the design choices that we make can improve access for all students.

Setting Expectations and Communication With Your Students

The Syllabus

Accommodations and accessibility shouldn’t be an afterthought; they should be transparently addressed and made visible from the very outset of the course, starting with the syllabus. Consider how you frame “accommodations” in your syllabus—is it infused throughout the syllabus, using language that communicates that you value the students’ various needs and welcome requests? Communicate to your students that you value accessibility, and invite them to communicate with you early on about any concerns they may have about their ability to participate in the course.

- When you design and then describe your learning activities and assessments, clearly outline what accommodations or alternatives are possible if the student is unable to meet the requirement due to limitations outside of their control.

- Find opportunities to give students agency in choosing their learning activities. This not only benefits students in need of accommodation, but also invites increased engagement for all students.

- Try to build in as much flexibility as your learning goals and course schedule permit.

- Consider, as well, breaking down larger projects into smaller parts or assignments, so as to allow for any issues to be addressed sooner rather than later.

Also make your communication policy clear in your syllabus, and stay consistent with it. Tell the students how you want to be contacted (Canvas, email, text, etc), as well as what to do in case of an emergency, along with what an emergency would consist of. Let them know as well how soon to expect a response from you.

Beyond The Syllabus

It is a good idea to outline the steps you have taken to address issues of accessibility and accommodation in each assignment and communication you share with students.

- Consider highlighting the link to transcripts to videos or other audio you assign, or assuring students that the documents you are sharing are screen-readable.

- It is also a good practice to survey your students in order to get a clearer understanding of their unique situations. Google Forms can allow you to create a survey which can include questions around connectivity and technology (you can use this student checklist as a model for possible questions), their timezone, other limitations on their time, and other stressors they are dealing with, as well as any other challenges they anticipate during the semester.

- Schedule a number of these kinds of check-ins with students throughout the course; we know that situations can change rapidly.

There is also an Accessibility Resources tab on every Canvas course site that you can point students to. As a faculty member, you are not responsible for addressing all the issues a student may face, but providing the information for students up-front and reminding them about that information periodically during the course again communicates to your students that you care about their well-being and success.

Apply Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Principles

The key assumption underlying UDL is that all learners are different. Being able to proactively understand and anticipate needs arising from such differences can help instructors remove unnecessary barriers to the accomplishment of the actual learning objectives. By providing detailed technical instructions, you remove an unnecessary barrier to learning.

UDL Principles

UDL outlines three key principles:

- Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

- Provide Multiple Means of Representation

- Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Providing multiple means of engagement focuses on the affect aspect of learning.

To address the wide variety of motivation and interests students bring to the course, UDL recommends that we provide different options for recruiting interest, sustaining effort, and self-regulation. An example:

For a final project of a class, the instructor allows students to choose the topic of their own interests. She scaffolds the final project into multiple milestones. For each milestone, she offers office hours to meet with individual students to discuss their progress and challenges. Through the office hours, she addresses students’ concerns, provides feedback, and guides students to reflect on their own work.

Letting students pick a topic of their own helps make learning meaningful. Scaffolding the final project helps students plan their work and progress towards the completion of the final project. Finally, office hours can help the instructor understand individual students’ aptitudes and challenges, and then customize their guidance accordingly.

Providing multiple means of representation makes content accessible for a broader range of students.

This principle asks instructors to provide options for perception, language, and comprehension. An example of providing options for perception is to include closed captions and transcripts for videos. Video captions/transcripts are necessary for making an audio accessible to students with hearing impairment (see instructions below). It also helps those who don’t speak English as their first language, those who don’t have enough Internet bandwidth to load the entire video, or those who simply prefer reading to watching. Finally, as students have different backgrounds and experience, it is important to provide options for comprehension. For example, using a visual aid to summarize a textbook chapter can be an effective alternative for enhancing students’ understanding.

Providing multiple means of actions and expressions addresses the differences in how learners navigate a learning environment and express what they know.

To achieve this, you need to provide options for physical action, executive function, expression, and communication. Students are different in their ability to execute the same physical action. For example, a student with diabetes may not be able to sit still for a three-hour exam and will be flagged as suspicious if you use Proctorio for an online exam. To solve this problem, you could break a three-hour exam into three one-hour exams and give students the option to choose the format that best suits their needs. Students may also differ as to how they demonstrate their understanding. A student who gets anxious and fails a timed exam may be an excellent writer. Thus, letting students choose assignments from several options can allow them to better demonstrate their understanding of course content. Building these options into your course design can help take the burden off individual students to self-disclose, while keeping lines of communication open gives them the opportunity to do so if and when they choose. This helps build community and sustain a sense of agency and engagement.

For more information on UDL, you can refer to CAST UDL Guidelines.

Designing for Accessibility Step by Step

Make Your Canvas Site Accessible

Use A Clean Page Layout

The layout of a page should be simple, clean, and uncluttered. Navigation should be clear and consistent from page to page. Pages and documents that contain many paragraphs should be chunked into sections to help learners navigate the text. In Canvas, use the “Headings” to create a logical structure.

You can read more about “Clear Layout and Design” and Semantic Structure: Regions, Headings, and Lists” for more information.

Provide Alternative Text For Images

Alternative (alt) text provides a textual alternative to non-text content. Doing so allows those who require visual assistance, those using screen readers, and those for whom the image doesn’t load, to derive meaning from the image. The alternative text must provide the content and function of the images within your page. (To learn more about how to provide meaningful alternative text, read Alternative Text from the WebAIM website).

Create Descriptive Hyperlinks

When adding a hypertext link, instead of pasting in the URL directly, attach the link to words that describe the link destination. When applying a hyperlink, the link should be attached to a phrase that tells the student where the link is going. Also, links should make sense out of context. Phrases such as “click here,” “more,” “click for details,” and so on are ambiguous when read out of context. (Read “Links and Hypertext” for more information)

Use Built-in List Generator In Your Content Editor

When listing items or points, it is important to use ordered (i.e. numbered or lettered) or unordered (bulleted) lists to structure your content in an accessible form. Avoid using asterisks, hyphens, or other marks as improvised bullets, as those are not rendered as lists by screen readers.

Choose Accessible Colors

Contrast and color use are vital to accessibility. Users, including users with visual disabilities, must be able to perceive content on the page. Do not convey meanings solely through colors. If you choose to use color, utilize the WebAIM Color Contrast Checker to ensure adequate color contrast and accessibility friendly colors.

Make Tables Accessible

Tables should be used for data display, not layout. A table is a data table when row headers, column headers, or both are present, while layout tables do not have logical headers that can be mapped to information within the table cells. (Read “Creating Accessible Tables” for more information.)

Provide Closed Captions and Transcripts For Audios and Videos

Captions not only benefit students with hearing impairment but also those watching videos in their non-native language. Some of the tools available to you such as Panopto and Google slides can generate auto-captions.

- If you are recording lecture videos in Panopto, use Panopto auto-captioning feature to generate closed captions.

- If you are recording lecture videos in Zoom, create a transcript. Transcripts are a great way to make your videos or audio materials accessible to all students. If you are recording a lecture through Zoom and want your audio to be transcribed, you can generate Zoom transcriptions. You can upload your transcript as an accessible PDF for students to read.

Provide Flexibility For Assignments & Assessments In Canvas

Providing flexibility for assignments and assessments is important for accommodating students with different learning needs. Below are different ways of accommodating students in Canvas:

Differentiate Assignments

Differentiated assignments allow instructors to accommodate students with different assignments or due dates. This is available in the assignment settings for online graded assignments, discussions, and quizzes.

- You can assign an assignment to individual students. You can also set different due and availability dates for a student within an assignment that is assigned to the rest of the class. Refer to “How do I assign an assignment to an individual student?” for detailed instructions.

- You can also allow students to resubmit their assignments to give them extra opportunities to improve their work. Here are the instructions for allowing resubmission of a Canvas assignment.

Moderate a Quiz

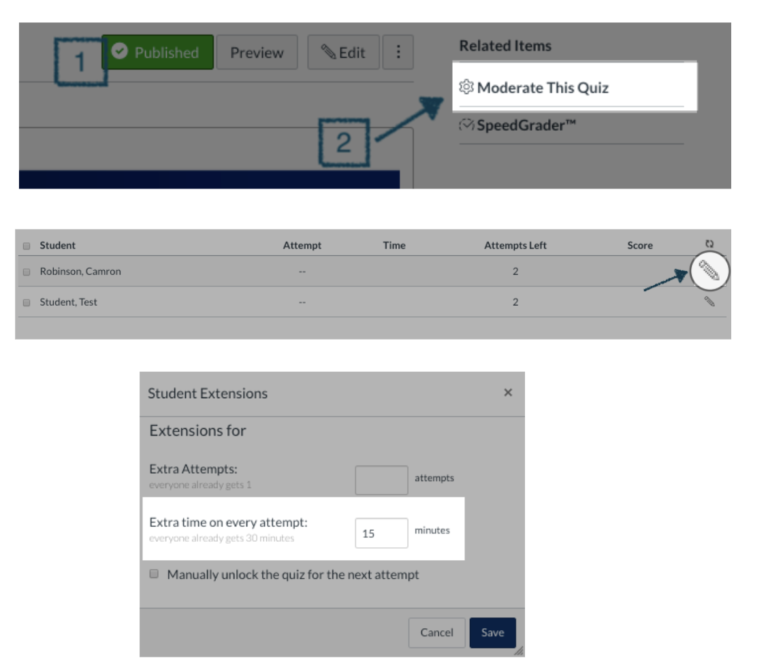

This setting allows instructors to adjust quiz settings for an individual or a subset of students. For example, they may give students extra attempts and time for a quiz. Check out Options in Canvas Quizzes for Accommodation for more details.

Faculty Insight

Providing Multimedia Transcript To Help Student Learning

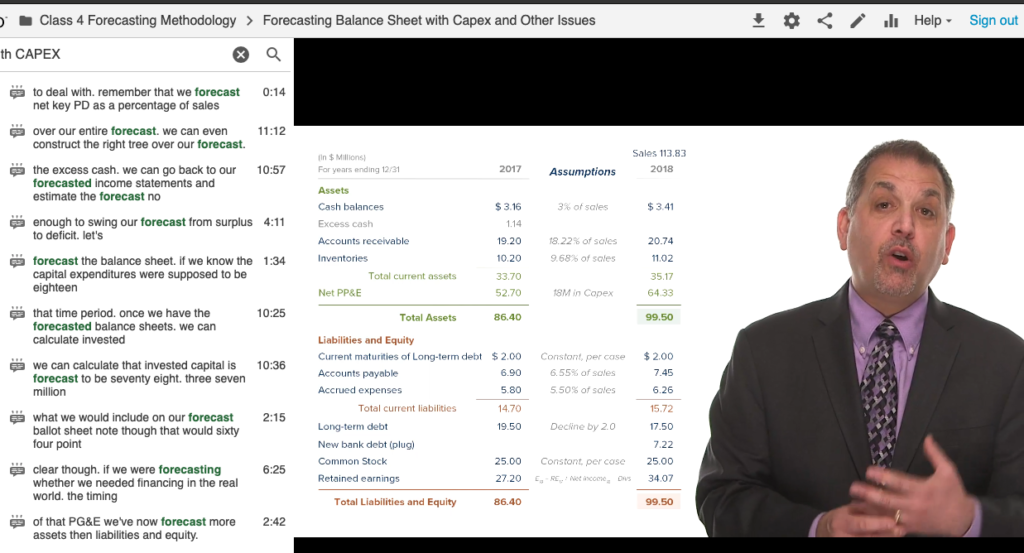

Professor Pinkowitz taught an Flex MBA class. 50% of the class sessions were online and 50% of them are in-person. He used Panopto as the platform for hosting his lecture videos for the online class sessions. For each of the videos, he provided closed captions and transcripts.

The closed captions in Panopto made his lecture videos accessible to students with hearing impairment. It also helped students who did not speak English as their first language. The closed captions in Panopto also allowed students to do keyword search, which helped them quickly navigate through the video. Finally, he created a multimedia transcript by inserting lecture graphics into the transcript. In this way, students could use transcripts as an alternative to the video without having to worry about losing important visual cues in the video.

Providing Multimedia Transcript To Help Student Learning

After publishing his quiz, Professor Michael O’Leary got to know that one of his students needed 1.5x time for a 30 minutes quiz. He accommodated the student by moderating the quiz.

Bibliography

Burgstahler, S., & Thompson, T. (Eds.). (2019). Accessible cyberlearning: A community report of the current state and recommendations for the future. University of Washington.

Burgstahler, S. (2020). 20 Tips for Teaching an Accessible Online Course. Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology.

CAST. (n.d.). UDL On Campus: UDL in Higher Ed. UDL on Campus.

CAST. (n.d.). About Universal Design for Learning. CAST.

Critical Design Lab. (2020, March). Accessible Teaching in the Time of Covid-19. Mapping Access.

LaGrow, M. (2017). From Accommodation to Accessibility: Creating a Culture of Inclusivity. EduCause Review. Educause.

Sasaki, D. (2020, March). Accessibility within Canvas. Canvas LMS Community.

Hallmark, E. (2019, September). General Accessibility Design Guidelines. Canvas LMS Community.